How we forgot how to treat scurvy, and other tales

We tend to think that knowledge, once acquired, is something permanent. Instead, even holding on to it requires constant, careful effort.

In the past few years, in the US, what was a fringe movement of anti-vaxxers has been gaining ground especially with Covid vaccination programs, a general mistrust of everything new, and divisive politics looking for issues to draw lines with. In India, while vaccine skepticism is unheard of, but so is questioning snake-oil-branded-as-ayurveda in the face of modern medicine. “I grew up without screens so can my child” is a common refrain with parents who grew up in the 1990s and are raising 2020’s kids, without regard for any of the positives that can super-charge learning for curious minds. And don’t even get me started on governments preemptively trying to slow down work in AI before they can even understand matrix multiplication.

All this makes me wonder how far we are from sliding back into a world with smallpox or rampant tooth cavity or increasing poverty and illiteracy. I mean, we can’t possibly go back to the Dark Ages, can we?

Turns out, it’s not an empty fear — unless we continue to prize finding truth above all else, and hold on to whatever little we have so far discovered with our dear lives. History offers repeated lessons, should we choose to pay heed. I’ll talk about five cautionary tales I know of, there must be countless more.

- Scurvy

- Schöder numbers

- Writing

- Much of science

- Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man

Scurvy

Scurvy is a horrible disease caused by a deficiency of vitamin C. Starting with inflamed gums, leading to gums becoming spongy and teeth becoming loose to arms and legs swelling up and becoming blackened around the joints to a painful death. We almost never hear of it except when reading about pirates.

Since the 15th century, doctors have known about it and how to keep it at bay even without understanding the actual underlying cause. Vasca da Gama’s crew in 1497 carried citrus fruits on their voyage and many doctors and sailors in the British East India Company often use it to have healthier voyages. In 1747 James Lind carried out an experiment to provide conclusive proof that citrus fruits cured scurvy, and quickly lemon juice became a compulsory part of the diet in the British Navy. So much so that it helped them win the Napoleonic Wars, and much of Sicily was converted into a lemon orchard for the British navy.

Yet, (I MEAN, YET!) in 1875, the British Arctic Expedition to the North Pole failed because of scurvy. In 1902, on the Discovery Expedition to the Antarctic, the crew developed scurvy and Shackleton barely made it back alive. In the acclaimed book The Worst Journey in the World about the 1910-1913 expedition to the South Pole, the author cites a Royal Navy surgeon advising the expedition that he had no better idea on how to deal with scurvy.

What happened? How did the world just FORGET how to cure such a terrible disease that killed millions of people (not just sailors and adventurers but many infants as well)? The answer lies in several factors:

-

The advent of steamships made the typical ocean voyage much shorter, and it was rare for sailors to be without fresh food for long, so Scurvy preventatives became less essential and easy to forget about.

-

With babies, particularly in wealthier families, pasteurization of cow milk led to less bacteria but also broke down the Vitamin C in the milk.

-

Medical authorities would make various assertions about Scurvy without any testing or basis in fact, like blaming contamination of preserved foods.

This is an excellent article on how it all went down: https://idlewords.com/2010/03/scott_and_scurvy.htm.

Schröder numbers

Schröder numbers are an important concept in combinatorial mathematics. They provide the solution to specific counting problems in different contexts, like lattice paths or parsing sequences. For example, counting paths in a plane that stay below a diagonal, or ways to insert parentheses into a string of symbols.

Take 10 symbols — a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j — and construct as many groups as you can by putting parantheses around 2 or more symbols, like this: ((a b) c d (e (f g)) h i j). There are 103,049 ways to construct such groups with 10 symbols — this makes 103,049 the 10th Schroder number.

They are named after the man who discovered these and published his results in 1870.

Turns out, the same number is written about by Plutarch, a Greek mathematician born in 46 AD, who credits Hipparchus, another Greek mathematician, born in 190 BC. It was only in the 1990s that someone found the connection and now these numbers are also called Schröder-Hipparchus numbers.

What was known in the 2nd century BC had to be re-discovered two thousand years later.

Writing

It is well known that Ancient Egyptians had a system of writing (hieroglyphs) that had been lost, and scholars have had to recreate their system from inadequate clues to understand their writing.

The book The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century lets us travel back in time a few thousand years. Right after the collapse of Ancient Egypt, the people there were still using hieroglyphs to decorate coffins and religious symbols. But people had forgotten how to write and their use of hieroglyphs spelled out nonsense!

How to write was only known to the elites scribes and priests, and as that group dwindled with foreign conquests and social unrest out, the population carried out the mechanical motions of writing without any deeper understanding. I wonder what we are doing today simply because the previous generations have been doing it, without attempting to understand it, and recreating nonsense instead. Reminds me of modern construction in India incorporating Vaastu into their design and architecture.

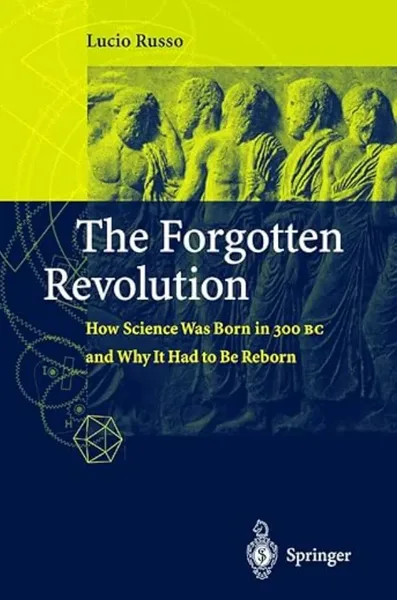

The Forgotten Revolution

The subtitle of this book — “How Science Was Born in 300 BC and Why It Had to Be Reborn” — says everything.

I’ll just drop a few quotes from the book and from Samo Burja who introduced me to the book.

From Samo:

Part of my thesis on Intellectual Dark Matter is that many of the momentus intellectual and ideological developments of the last three hundred years happened in previous civilizations as well.

From the book:

The naive idea that progress is a one-way flow automatically powered by scientific development could never have taken hold, as it did during the 1800s if the ancient defeat of science was not forgotten.

In recent years, we have taken civilizational progress for granted, and assume we will continue on a linear trajectory.

in face of a general regression in the level of civilization, it’s never the best works that will be saved through an automatic process of natural selection

We assume past civilizations to be less advanced, and fall prey to the fallacy that the archaeological remains must represent their best or peak work. One of my favorite takes on this is this tweet:

“For 1500 years we forgot how to make a device as complex as the Antikythera Machine. And we also became surprised people 1500 years ago could. I think that regression also creates strange assumptions about technological development.”

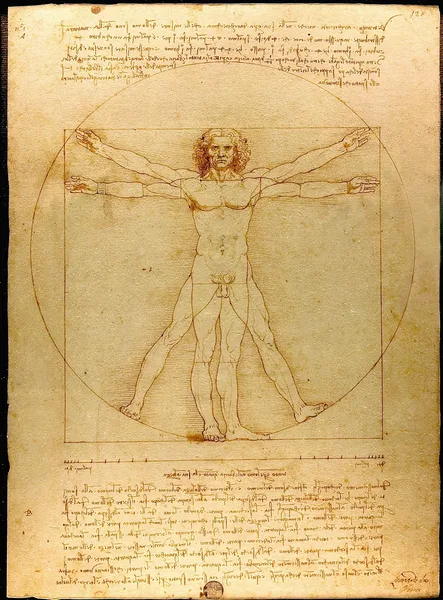

The Vitruvian man

One of Leonardo Da Vinci’s most famous works is The Vitruvian Man. Even if you don’t know it by name, I’m sure you’ve seen the photo of a careful drawing of a nude male figure spreadeagled in two superimposed positions inside both a square and circle.

Around 1490, Milan’s authorities were looking for ideas to build a tower atop their cathedral and set it up as a public competition. Da Vinci, the ever polymath, used this opportunity to study and establish himself as an architect. In his exploration to develop a methodology for aesthetics and proportions he chanced upon the works of Vitruvius.

Vitruvius was born in 80 BC, served in the Roman army under Caesar in design and construction, and later became an architect. His only surviving work was literary, about the design of temples and aesthetics and proportions and how they ought to relate to the proportions of the human body. Rediscovered in the early 1400s, his writings were included in the collection of classical works in Florence that gave birth to the Renaissance.

Da Vinci based his drawing of the Vitruvian Man upon these writings of Vitruvius, influencing his ideas of proportion and beauty and architecture. Thus, forgotten work until (then) recently for over a millennia became a core part of Renaissance architecture and a large influence on our culture today. Vitruvius’ singular surviving work could have just as easily not survived or remained undiscovered.

Takeaways

These stories drive home a few realizations for me:

-

Older civilizations were likely much more advanced than we give them credit for.

-

How wrong is the principle of the Lindy Effect? It might be true for jokes in a comedy club but extending it to every idea or practice in humanity seems to be fraught.

-

The scariest thing in the world is when those with authority espouse ideas without any grounding in fact or science or when they resist testing new ideas.

-

Some times new technology reduces widespread application of certain pieces knowledge, and that can easily slide from our collective memory.

-

Our civilization can die out too. How can we preserve what we have for future ones? Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series has such resonance with this question.

-

Knowing history is really fucking important.