Creating product metrics

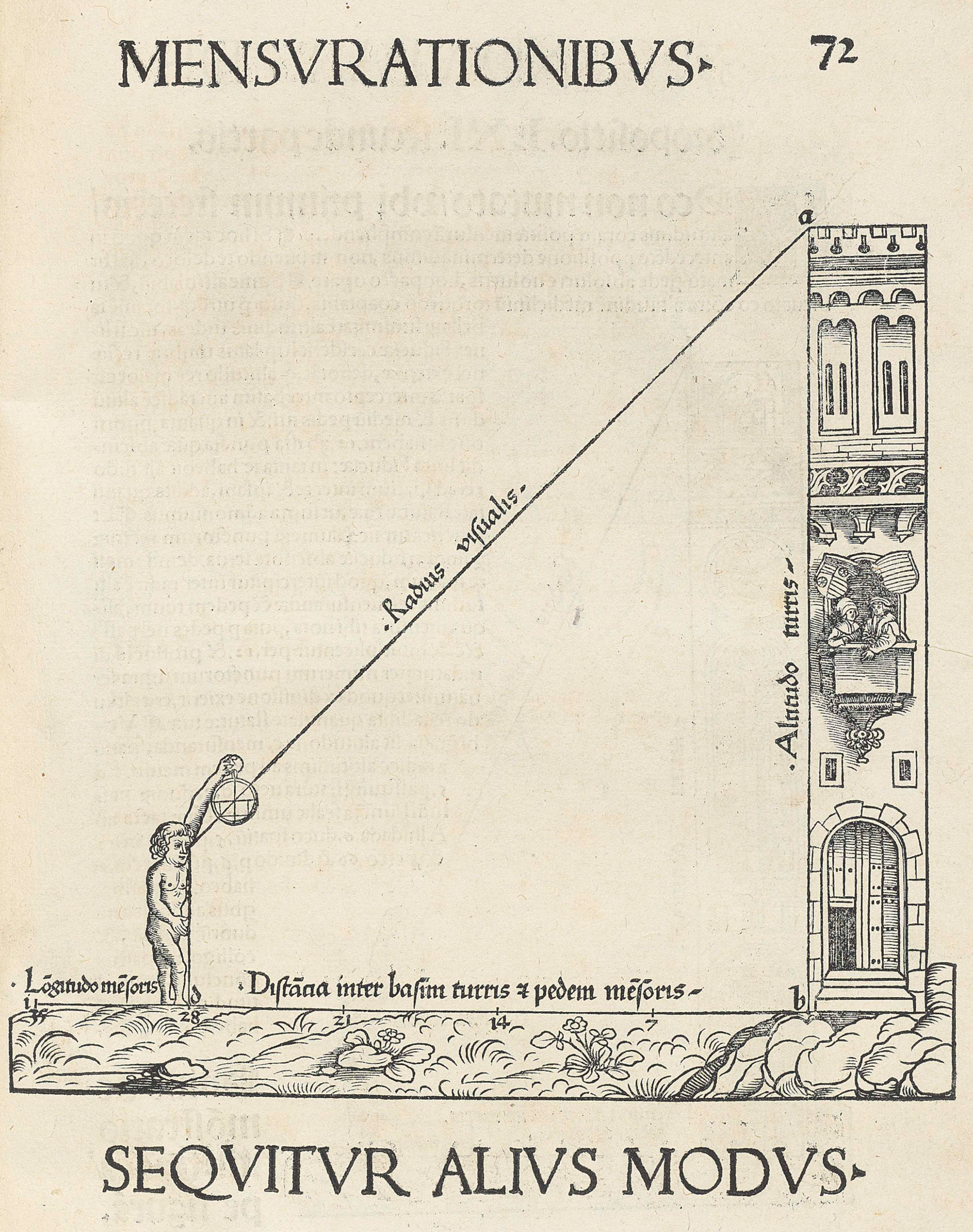

Nearly three thousand years ago we figured out how to measure things indirectly — the height of the pyramids of ancient Egypt, for instance, where one couldn’t simply walk down and count the number of paces. Triangulation and concepts derived from it continue to be used for everything from surveying land to pinpointing our location on Earth using the signal from three different GPS satellites.

In measuring product and user behavior too, we have to triangulate our way to the truth using multiple metrics.

Few metrics mean anything on their own — metrics are useful only when in a collection with other metrics that can provide multiple lenses into product or user behavior. This post talks about some principles for selecting and using metrics and some practical guidelines on creating a system of metrics for your product.

A single metric is only a reference point and you need multiple reference points to triangulate your product bearings, i.e. truly understanding what is going on in your product. Even something as widely adopted as DAU (daily active users) is not easily interpreted on its own — if an app has 1 million DAUs, it tells you nothing about how engaged they are, or how frequently they use the app, or how soon they may churn out, etc. Without answering these other questions, the DAU number by itself does not paint a complete picture of usage.

What is a system of metrics

It is simply a set of metrics that fit together like jigsaw pieces to give you a complete view of your product.

To do this, this system needs to get a few things right: it should be able to give you early warnings on user behavior in either direction, it should have reliable milestones of progress towards your north star that cannot be gamed, it should have blind-spot detectors for the system itself.

We will dive deeper into all of these later in the post, but first, let us lay down the goals of such a system of metrics.

Purpose of metrics

When creating something it is best to first lay down its goals so we can design it accordingly. Product metrics, in the collective, should help you achieve three things:

🎯 1. Ground truth

The foremost and obvious benefit of metrics is to help you find the ground truth about your product — what your users are doing in the product, how your product is behaving. They enable you to monitor your product and business, and understand what to expect in the future. They help you make better product decisions — how to prioritize your roadmap, what features you can deprecate, how to meet your goals.

🎬 2. Storytelling

Numbers are a powerful storytelling aide. They make abstract concepts concrete. They provide a common vocabulary to people which helps bring them together in a shared narrative. They lend credibility to your vision.

Early internet companies used to tell their growth story to the outside world using visitor counts, analogous to foot traffic from the real-world. Over time, as an industry, we have realized our capability to have far more sophisticated data and insights and it reflected in the stories — visitor counts evolved to registered users and then to Monthly Active Users and Daily Active Users, in addition to building a common parlance around churn, retention, acquisition costs and lifetime value, etc. Each step was in service to a more compelling narrative.

Even at the very earliest stages of your growth, you will find yourself needing to present the work of your team, explaining why the work of your team is important at different forums: at an all-hands, a board meeting, with investors, at conferences. The common vocabulary across audiences is that of numbers and charts — metrics that are intuitive and can summarize human output are great tools in these instances.

A good system of metrics helps you identify the right metric for the right message and gives you the surrounding lenses through other metrics to fortify your story. For example, “We are in a good spot with growth even though new acquisitions have slowed, it is because paid acquisitions are down but retention for the organic cohort is increasing” is something any investor would like to hear but needs a number of data points to make it watertight.

🏗 3. Operational scaffolding

Metrics create organizational legibility. As a company scales, one of the toughest challenges for a founder is that of understanding what is happening in different parts of the company, how effective every team is, and providing direction through formal goals.

Metrics act as levers through which you can direct different parts of your organization. Even in the very early stages, when your “organization” can all fit in a single conference room or single Zoom panel, a language of metrics allows you to create a culture of objectivity, transparency and ownership. It sets the stage for scaling more easily later.

A non-obvious example of this playing out in practice is in consumer products that generate revenue via ads: they need to continuously make tradeoffs between driving ad revenue and consumer engagement as the two can be at odds with each other. Having metrics for how frequently ads are shown, the revenue associated with an increase or decrease in this frequency, the expected consumer engagement impact, allows for objective decision making in finding this balance. This becomes especially critical when two sides of the product are trying to meet competing targets.

The right metrics can enable your teams to reason about such tradeoffs and arrive at an acceptable conclusion without needing subjective decisions from you!

Where to begin

Creating a system of metrics for a new product or feature should look like an exercise in Google Docs or <insert your favorite writing tool here>, and not as an exercise in Amplitude or <insert your favorite analytics tool here>. Metrics are ultimately a way of describing how your product is functioning and what utility users are getting from it. Before you get to the numbers, it is important to get to it in words.

✍️ Start with an audit: list all the major components of your product and for each, ask yourself:

- How do you define success? What is the impact this product should ultimately have?

- How would users use the various features? What actions would you like them to carry out? UX flows and progress through a funnel can come here.

- Is there any systemic behavior you expect, that would be invisible from the outside? Things like network effects or marketplace efficiency or growth are not visible through a user-lens, so this is important.

- What behaviors (either of the user or the product) suggest users might be stumbling? In B2B products, customer support tickets are a clue of these stumbles, for example.

Answering these questions will help you identify multiple metrics that offer evidence for each. If the answers start looking like the essence of a product spec, you are doing this right! Ideally, metrics should be a part of the spec and put in place along with building the product.

✂️ The second step of this process is the hard part. You will inevitably end up with dozens of metrics and will need to whittle them down to a manageable list. Both building the metrics (data pipelines, processing, etc) and analyzing a large number of them are effort-intensive and not a luxury that lean teams can afford. Plus, when you’re a small team, you have to maintain focus and not try to move all the metrics all the time. What are the most important metrics that your team can act on?

To understand the scale here: products like Twitter and Instagram have hundreds of metrics along with a team of data scientists responsible for creating, maintaining, and analyzing them. They use sophisticated tools to automatically identify important metrics and how different metrics correlate with each other. Even so, it becomes challenging for a single team to incorporate more than a handful of metrics into their regular operating cadence and build intuition for the numbers.

While there are great off-the-shelf analytics tools out there, they tend to lack the sophistication of custom tools that these large companies have built internally. Smaller companies cannot invest valuable resources into building similar internal tools, but can avoid pitfalls of third party tools by having a sound system of metrics created from first principles.

Selecting the right metrics

Not everything that can be measured should be a metric. A useful system of metrics is concise but provides high coverage. This section describes the characteristics of a good system, and how to select which metrics your system should include.

🐢 1. Lagging indicators

Lagging indicators tend to measure behavior that you cannot influence directly. They move slowly and in smaller increments, so they are harder to observe, like the last few ripples when a stone is thrown into still water. They better withstand misplaced incentives, are a more reliable signal across a larger surface area and tend to be measures you can use over a long period of time.

Goodhart’s Law (from the British economist’s writings in 1975) captures the essence of lagging indicators: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”.

Metrics like DAU, MAU, Churn rate are common lagging indicators for consumer products. Net Revenue Retention is a common lagging indicator in B2B products. For well-understood products, lagging indicators become industry standard over time, and you will find your investors already asking for those metrics. Products in new and less understood categories may have to break the mold and create new lagging indicators that serve them better.

🐇 2. Leading indicators

Leading indicators are more direct windows of observation; they help you observe changes quickly because they are the most sensitive and swing farther in response to changes. Leaning on the analogy of a stone thrown into still water again, these are like the first ripple that emerges.

This makes them great for early warnings, running a/b tests, and focussing on narrow parts of the product.

Picking the right leading indicators is harder than finding lagging indicators, and more important to get right early on — they serve as headlamps in the dark. The famous “10 friends in 7 days” from Facebook’s early growth days is a great example: once they understood this was the right leading indicator for retention, they were able to orient entire teams to focus on this.

Good leading indicators are ideally causally related to the lagging indicators: if a leading indicator moves, that should eventually result in the lagging indicator moving. Sometimes the relationship is simply sequential, like in the case of a user funnel: if click-through rate increases on an Add To Cart button, it will very likely lead to overall purchases increasing.

But at other times the relationship is not obvious and you may have to find it by induction or causal inference (statistical methods to do this in a rigorous way). This is how Twitter found that increasing engagement in the Home Timeline (a leading indicator) was causally related to DAU (a lagging indicator): users would be more likely to return the next day the more they saw tweets they liked, retweeted, or replied to today.

⚖️ 3. Counter-metrics

Counter metrics allow you to observe unintended consequences of your product decisions, and serve as checks and balances when you are focussed on driving certain key metrics.

If an e-commerce site has an add-to-cart button, you could make a reasonable guess that increasing clicks on that button would lead to more sales. And then you would task a small team with that one goal: increase clicks on the Add To Cart button. If so incentivized, there is a product/design space any smart team will stumble upon that will lead to increased clicks on that button but not necessarily revenue. A trivial example is by making the click target on the button larger, which is likely causing accidental clicks.

To prevent such mistakes — inadvertently or due to misaligned incentives — counter metrics are essential to act as blind spot detectors as you focus on driving one or more leading indicator metrics.

Reducing friction in a sign up flow? Check to see how much of the increased sign ups are spam. Put a Contact Us button on a website to reach sales? Check to see how much of the contacts are actually people looking for customer support. Added graphics on a page to increase conversion? Check for increased page load times.

🫶 4. Attitudinal metrics and other evidence

Jeff Bezos famously said: “The thing I have noticed is when the anecdotes and the data disagree, the anecdotes are usually right. There’s something wrong with the way you are measuring it”. This is not a disavowal of data — it is an affirmation of needing to consider “evidence” holistically. No matter how good your observability, data that gets logged has blind spots that you need to be checking.

Allow other feedback channels to be visible along with your metrics: customer support tickets, surveys, anecdotes via sales or account management, discussions on reddit, twitter, stack overflow, etc.

In addition to what users are doing in your product, you need a lens into how they feel while using your product. Emotional needs are as important as functional needs, especially for consumer products. And behavioral metrics can never capture that. This makes it necessary to create a set of Attitudinal metrics that can summarize more subjective input from users, captured using a range of tools from structured surveys to simple thumbs up / thumbs down buttons in your product. You want to know when confusion, frustration, fun, sense of trust, etc. are trending in the wrong direction.

A system of metrics is never static — the cycle of teasing out insights from data, discovering new blind spots and creating better observability is ever ongoing.

Common mis-steps

“It is wrong to suppose that if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it — a costly myth.” —W Edwards Deming

“What gets measured gets managed — even when it’s pointless to measure and manage it, and even if it harms the purpose of the organization to do so." —Peter Drucker

The biggest pitfalls in using metrics stem from overzealousness of wanting to measure everything in numeric terms. Here are three that run contrary to convention:

🙅 1. NPS

Net Promoter Score is a deceptively simple concept: how likely are your customers to refer your product to their friends? The challenge comes in taking this square peg of a reasonable abstract concept and shoving it into a number-shaped round hole: it breaks down in unexpected ways.

Firstly, the score itself is a convoluted calculation: “% of promoters - % of detractors”. That number has no intrinsic meaning, nor is it helpful in watching it move up or down. Almost always you need to look a layer or two deeper to understand which customers are happier or unhappier.

Relatedly, as a survey, this is simply too broad a question to give you actionable insight. Almost always NPS surveys need to be accompanied by more detailed questions, and if you are running a full survey, you are better off relying on answers to the other questions than looking at NPS.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, NPS is not always predictive of future growth. Products often start measuring NPS without ascertaining causality with their customer retention. There are many counter examples where an unpopular change made to a product eventually became a large growth driver — Facebook’s News Feed was one, Twitter’s algorithmic timeline (disclaimer: I helped build it) was another — it resulted in the hashtag #RIPTwitter to trend as some users resisted the change, but the data clearly showed that a majority of users were using Twitter more because of that change!

Avoid NPS, and use simple surveys to understand customer sentiment and satisfaction, and drivers of that.

🙅 2. Time as a metric

What is the purpose of technology but to save us time from inane tasks and then have us spend all that time on other things enabled by technology! It makes for a good directional goal for user-facing software. For example:

- API products might aim to help developer build something in less time, or

- Productivity tools might aim to help corporate employees do a task in less time, or

- Consumer products, especially in media and entertainment, might want their users to spend more time on their platform.

Time is one of the most important resources for people, and a product being able to influence how or where we spend our time is almost always a hallmark of success. However, it does not translate well into a metric.

Time is hard to measure — for instance the time taken for a developer to build an app using your platform can have many confounding factors that you don’t have visibility into. Secondly, it can be misleading — if a consumer is spending more time in your app is that good? Are they spending that time in a valuable (to them) way? If they are spending less time in your app is that good? It can be hard to tease apart whether that time is well spent or not.

Watch time is a common metric that video or media products often cite. One reason why is that the traditional advertising industry uses it, and it makes sense to talk in the language of your customers (if you are selling to advertisers). But it is not useful when it comes to guiding product development. A recent WSJ article about Instagram Reels reported users spending ~18 million hours a day watching Reels vs ~198 millions hours a day spent on TikTok. What would you take away from those numbers? It does indicate TikTok videos are a larger consumption platform than Instagram Reels but tells you nothing about the user base, level of engagement, other consumption behaviors in Instagram since all of TikTok is video but not all of Instagram is video (watch time here not even a fair comparison!).

What most people want to measure when they try to measure time is utility, and utility can be measured in other ways: valuable actions taken in your product, transactions completed or revenue, or surveys to get some qualitative signal.

🙅 3. Synthetic metrics

It often starts out with the desire to reduce 10 different metrics into 1 to make for easier reporting: What if we combined the number of errors and number of support tickets and number of drops in the funnel to create a metric called “failures”? What if we took all the clicks on a post and created a single metric called “engagement”?

It is tempting to aggregate different numbers that may be conceptually related, but it is a treacherous path. Teams end up spending a lot of bandwidth on finding the right roll-up, on building intuition for a number, on educating the rest of the organization on a new, hard-to-grok number (”the overall failure metric has gone up from 126 to 142. What does that mean? How bad is it?”)

The best metrics are the simplest, where the values make obvious, intuitive sense. Synthetic metrics obfuscate more than they reveal, and if they are created to simplify reporting outside the organization, they are an endless source of confusion.

Where to go from here

Now that you have (hopefully!) a good understanding of how to make metrics work for you, it’s best to dive right in and start creating a set of metrics for your product. Start by modeling out your product and business, the most important outcomes and levers, and then pick metrics that would give you insight into the nuts and bolts. Here are some excellent articles that go into detail about metrics for different kinds of products and businesses, and can help you find a good starting set:

- Metrics vs Experience by Julie Zhuo

- Choosing Your North Star Metric by Lenny Rachitsky

- 11 Key GTM Metrics for B2B Startups by Martin Casado

- 13 Metrics for Marketplace Companies by Jeff Jordan, Li Jin, D’Arcy Coolican, Andrew Chen

- 16 Ways to Measure Network Effects by Li Jin, D’Arcy Coolican

- Is anything worth maximizing by Joe Edelman

The next thing to do, once you have some numbers (whether on a dashboard or in a spreadsheet) is to start reviewing the numbers with your team. Data is only useful if it is being interpreted, questioned, and acted upon. A regular review also shines light on which numbers are useful, which are not, where you might need to add more metrics, and help you evolve the system.

This post has a good overview of what metric review meetings look like at large organizations that have a rigorous, data-driven culture.

- A Leader’s Guide to Metrics Reviews by Sachin Rekhi

As a startup, you might prefer to avoid much process early on but the hygiene of asking questions about the data, following up on unanswered questions and presenting new finds at this forum regularly is good to establish early on.